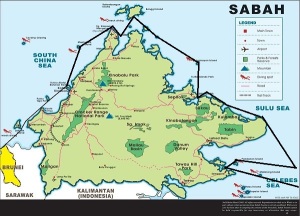

Travelling north from Bruneii and Labuan is definitely revisiting the past except this time we got to sail back to KK in a brilliant following breeze, well 25 knots that had the locals ducking for cover behind every island. Back in KK the word was engine repairs and yet again pondering heat exchangers and a crew change with Lasse leaving and German Sebastian coming on for the passage across the Celebes Sea to Davao in the Philippines. Before all of this though we decided to head out to Gaya for some diving and beach timeand to see if we could sneak past the enjoyment police at the resort, without paying for multiple guides to follow us around on the national park tracks. Simon was with us this time to show us the sneaky way past the resort people but to no avail as when we were spotted they couldn’t understand Lasse’s Swedish or for that matter Geoff’s Welsh, no surprises there really! So it was off on the national park tracks (the guides are really to allow you through the resort it seems) and a visit to the resort, forest, canopy walk.

We had come through here a year or so earlier and whilst managing to get a swim in the resort pool and even being given a free cocktail (quite accidental on the resorts part) we were told very clearly to anchor to the sides of the bay. It seems a view of grotty yachties and their boats detracts from the whole resort experience or something. So to avoid any angst we slipped over to the south side of the bay and Trevor parked the Gadfly on the mooring that we had swung on last time before heading for Layang Layang; in this case a nice fat rope attached to a big-arse coral pinnacle on the bottom. Sadly the coral wasn’t up to the job as that night a squall to take ones breathe away hit us and with the boat nearly on it’s side in 50 knots of wind the mooring let go. Bit of a worry really, 2.30 in the morning, pitch black and in wind and rain one cannot look into the boat is bouncing up and down on the reef. Well when in doubt look for sea room so off into deep water we went dragging the bottom of the boat across the reef only to work out we still had a sodding great lump of coral hanging from the front of the boat, oh joy. To make matters worse our snubbing rope was now tangled in the mess of mooring line giving the appearance of a ‘Gordion’ knot. Ah well, these squalls do blow themselves out so eventually with the wind subsiding we deposited the resort’s mooring in a new location and went on the pick in the middle of their bay.

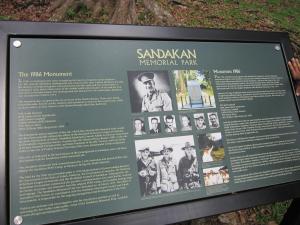

Back in KK after sorting various repairs and some new awnings for the cockpit we headed north hopefully for some diving with the new Hookah (surface supply compressor). It was also back into some old haunts of Lankayan , Sandakan and Kudat where we caught up again with the Rubicon Starlets (Tim and Barb). On Lankayan they had built a great big and beautiful new restaurant and bar just for us it seemed and we spent a couple of days here snorkelling,  diving and seeing the sights. Sandakan of course remained the same right down to the foul ground and fasteners out in front of the yacht club. Last time we were here the anchor was turned inside out courtesy of some fishermen helping extract it and sure enough this time we fouled again, this time on whopping great sunken fishing boat. We were actually anchored well clear of all the fasteners but dragged in a squall and spring tides and after dragging into the , tide changes figure-eighted the chain a couple of times in and over the wreck. Geoff had a go at getting it off first and

diving and seeing the sights. Sandakan of course remained the same right down to the foul ground and fasteners out in front of the yacht club. Last time we were here the anchor was turned inside out courtesy of some fishermen helping extract it and sure enough this time we fouled again, this time on whopping great sunken fishing boat. We were actually anchored well clear of all the fasteners but dragged in a squall and spring tides and after dragging into the , tide changes figure-eighted the chain a couple of times in and over the wreck. Geoff had a go at getting it off first and

came up rather wide eyed as there really is nothing like diving in zero visibility, with current, on a wreck with all sorts of ‘things’ washing past; south-east Asian ports are not the most aesthetically pleasing places to dive in. We eventually got our chain off with Trevor grovelling around on the bottom wrestling chain from behind steel plates and fishing nets and in the dark although one doubts the bottom here has seen sunlight for a long time anyway. Handy to have the hookah at this point and all but in the absence of a full-face mask there was considered thought to what new vaccinations might be in order!!

came up rather wide eyed as there really is nothing like diving in zero visibility, with current, on a wreck with all sorts of ‘things’ washing past; south-east Asian ports are not the most aesthetically pleasing places to dive in. We eventually got our chain off with Trevor grovelling around on the bottom wrestling chain from behind steel plates and fishing nets and in the dark although one doubts the bottom here has seen sunlight for a long time anyway. Handy to have the hookah at this point and all but in the absence of a full-face mask there was considered thought to what new vaccinations might be in order!!

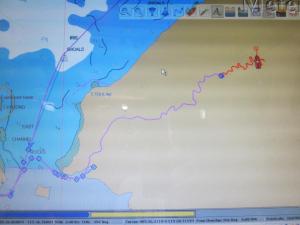

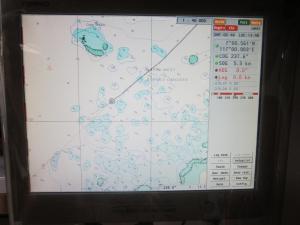

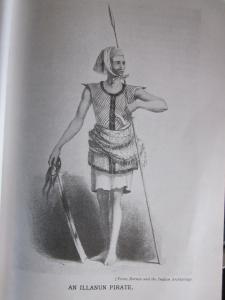

Moving east was back through familiar territory, Dewhurst Bay, Tambisan, TunSakaran and Semporna. We did head direct from Tambisan towards Davao but a friendly Philippino fisherman suggested we shouldn’t go past a couple of islands as “they are pirates”, “very bad people”, “Abu Saiaf”; okay we will go the other way back to Semporna! So a few days later it was off on the 400 odd miles across to Davao and back into the Philippines. This involved three nights at sea in what was pretty calm and easy conditions except for hundreds of unlit navigation hazards. Daryl on Metana had given us a heads up on this and it seems this whole part of the Celebes Sea is used for fishing with FAD’s or Fish Attraction or Aggregation Devices. There are hundreds of them, whopping great steelbouys about 6 metres long and anchored in anything from 100 to 5000 metres of water. Local fishermen work the FAD’s with boats all over the place including one fellow 20 miles offshore in his rather small ‘banka’ asking us if we wanted to buy his dolphin fish. It seems the dolphin fish hang around the bouys and assorted palm fronds and such things that the fishermen attach to the bouy and rope underneath. At night these things are a worry, they only paint up on radar in smooth water at about half a mile and even when a fishermen is tied up at night to one, they only turn their light (flashing disco style) on when they a see a boat close by. Apparently they don’t want to flatten their batteries, makes interesting night passages in this part of the world!!

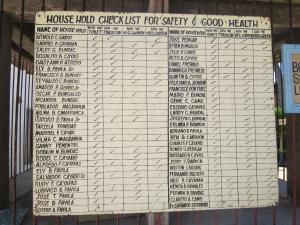

First port of call on this new Philippino adventure was Bulot Island at the bottom of the Davao Gulf, a visit to the town then some of the islands for snorkelling, swimming and visiting the locals. At the island across from Bulot the locals were very keen to investigate (don’t see too many yachts in these parts it seems) and we eventually had half of the little beach community on the boat for lunch. They even helped us clean the water line on Gadfly and thereforegave us an opportunity to  give away ‘cargo’ that meant much to them and good kharma for us; old sunglasses, monofilament not used for two years, old ropes, redundant stainless pots and crab traps amongst other things; these are very poor people. We day hopped the hundred odd miles into Davao eventually going into the marina at the top of Samal Island just over the water from Davao town. Not many good anchorages here as the beaches are all quite steep to with deep water. Did let us see how the locals get by though and when swinging on a postcard of shallow water near the reef in one bay we could watch the locals carting on their backs loads of copra (coconut husk) in sacks to lighters that then carried the sacks to boats further out. They do it tough in this part of the world. On other boats here the ferries across from Samal are interesting with an ‘engineer’ sitting aft responding to the helmsman via a ‘telegraph’, in this case a steel bar banging on a metal pipe when the helmsman tugs on a piece of string; love it!

give away ‘cargo’ that meant much to them and good kharma for us; old sunglasses, monofilament not used for two years, old ropes, redundant stainless pots and crab traps amongst other things; these are very poor people. We day hopped the hundred odd miles into Davao eventually going into the marina at the top of Samal Island just over the water from Davao town. Not many good anchorages here as the beaches are all quite steep to with deep water. Did let us see how the locals get by though and when swinging on a postcard of shallow water near the reef in one bay we could watch the locals carting on their backs loads of copra (coconut husk) in sacks to lighters that then carried the sacks to boats further out. They do it tough in this part of the world. On other boats here the ferries across from Samal are interesting with an ‘engineer’ sitting aft responding to the helmsman via a ‘telegraph’, in this case a steel bar banging on a metal pipe when the helmsman tugs on a piece of string; love it!

Of course as always on ones own boat boats things rarely go according to plans and in this case after arriving at the Samal marina Trevor decided to work out what that oil leak was all about. Well we arrived on the Wednesday and on Friday we pulled the engine out of the boat, ah yes, boat maintenance in exotic locations. Sorry about the delay in news. Cheers from the Gadfly.

Fish Attraction (or Aggregation) Devices.‘FADs’.

A fish aggregating (or aggregation) device (FAD) is a man-made object used to attract ocean going pelagic fish such as marlin, tuna and mahi-mahi (dolphin fish). They usually consist of buoys or floats tethered to the ocean floor with concrete blocks. Over 300 species of fish gather around FADs. FAD’s attract fish for numerous reasons that vary by species.Fish tend to move around FADs in varying orbits, rather than remaining stationary below the buoys. Both recreational and commercial fisheries use FADs.

Before FADs, commercial tuna fishing used purse seining to target surface-visible aggregations of birds and dolphins, which were a reliable signal of the presence of tuna schools below. The demand for dolphin-safe tuna was a driving force for FADs.

Fish are fascinated with floating objects. They aggregate in considerable numbers around objects such as drifting flotsam, rafts, jellyfish and floating seaweed. The objects appear to provide a “visual stimulus in an optical void”, and offer some protection for juvenile fish from predators. The gathering of juvenile fish, in turn, attracts larger predator fish. A study using sonar in French Polynesia, found large shoals of juvenile bigeye tuna and yellowfin tuna aggregated closest to the devices, 10 to 50m. Further out, 50 to 150m, was a less dense group of larger yellowfin and albacore tuna. Yet further out, to 500m, was a dispersed group of various large adult tuna. The distribution and density of these groups was variable and overlapped. The FADs were also used by other fish, and the aggregations dispersed when it was dark.

Drifting FADs are not tethered to the bottom and can be natural objects such as logs or man-made.

Moored FADs occupy a fixed location and attach to the sea bottom using a weight such as a concrete block. A rope made of floating synthetics such as polypropylene attaches to the mooring and in turn attaches to a buoy. The buoy can float at the surface (lasting 3–4 years) or lie subsurface to avoid detection and surface hazards such as weather and ship traffic. Subsurface FADs last longer (5–6 years) due to less wear and tear, but can be harder to locate. In some cases the upper section of rope is made from heavier-than-water metal chain so that if the buoy detaches from the rope, the rope sinks and thereby avoids damage to passing ships who no longer use the buoy to avoid getting tangled in the rope.